How to Use Social Norms Like A Pro

Behaviour is heavily influenced by our perception of social norms. Our answers to questions like "What are other people doing?", "What's normal?", and "What's approved of?" go a long way to shaping our own behaviour—often more than we realise.

An intervention that changes our perception of the prevailing norms is likely to change our behaviour. A simple and reliable way to do this is just to give people information about what the people around them are doing. This has made the 'social norm message' a staple of the nudge toolbox.

These messages have increased timely tax payment ("9 out of 10 people pay their tax on time"), reduced overprescription of antibiotics by doctors (telling the most prolific prescribers that they are well above average), and even moderated college students' drinking habits.

Not all social norm messages are equally persuasive, however. Nor are they equally available: in some contexts, it just won't be the case that most people are already doing the desired behaviour, taking "9 out of 10 people"-style messages off the table.

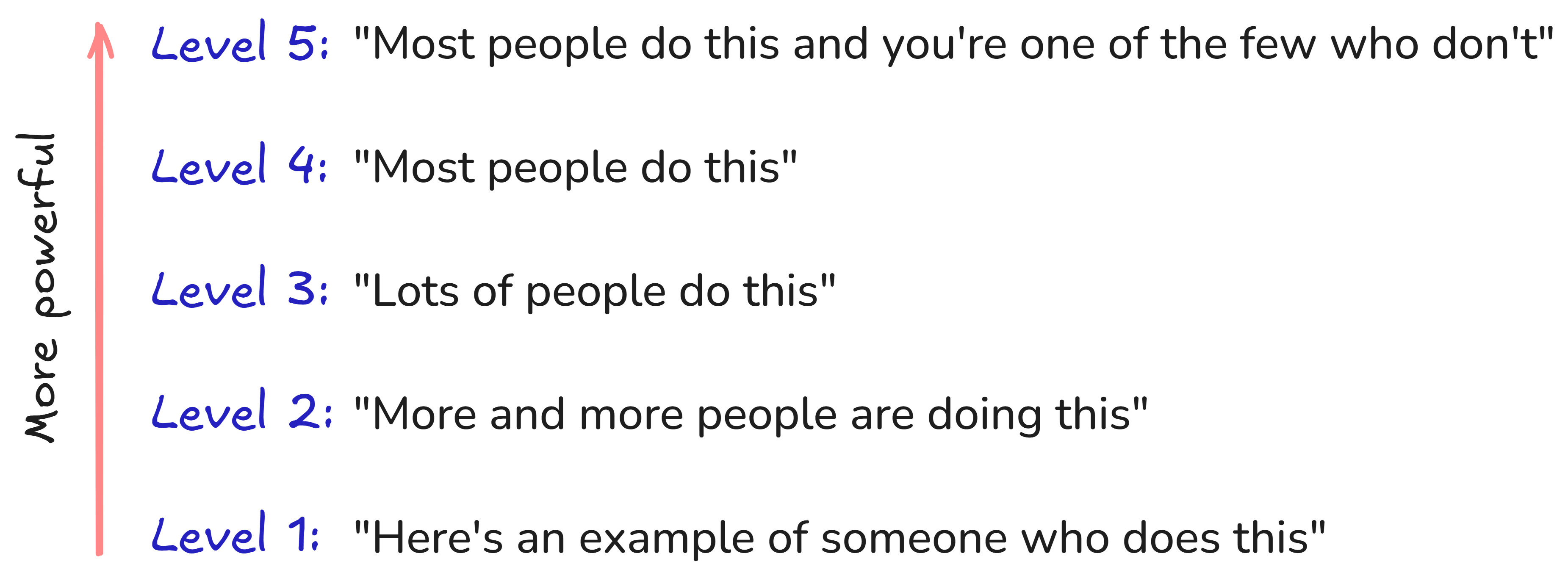

As you think about deploying social norms messages yourself, you will generally want to reach for the most persuasive true message available. Below is a rough hierarchy:

Most people do this...

A straightforward and powerful social norm message is to inform people that most others do the desired behaviour. This majority doesn't have to be huge as long as it's true and credible. In Guatemala the number is only 6 out of 10, but that is still higher than people expect: telling them was enough to significantly increase payments.

Where possible you should tailor the social norm to the groups that people more strongly identify with. In the tax example mentioned above, sharing a local norm ("9 out of 10 people in [town you live in] have paid their tax on time") was more persuasive than the national norm ("9 out of 10 people in Britain..."). If you want a small business owner to sign up for a trial of your software product, it's more persuasive if you can share tailored information about how peer businesses similar to them—in their industry, or of similar size—are getting on with it.

A common tactic is to present these statistics is as 'natural frequencies' rather than percentages—that is, '9 out of 10' rather than '90%'—as the former are thought to be slightly easier to grasp. This is inspired by research by David Spiegelhalter on how people understand probabilities, although I'm not aware of a study that conclusively proves this out in the social norms context.

...and you're one of the few who don't

A social norm message becomes even more persuasive if you can show people that their current behaviour is outside the norm in some way, particularly where they wouldn't otherwise know that that was the case.

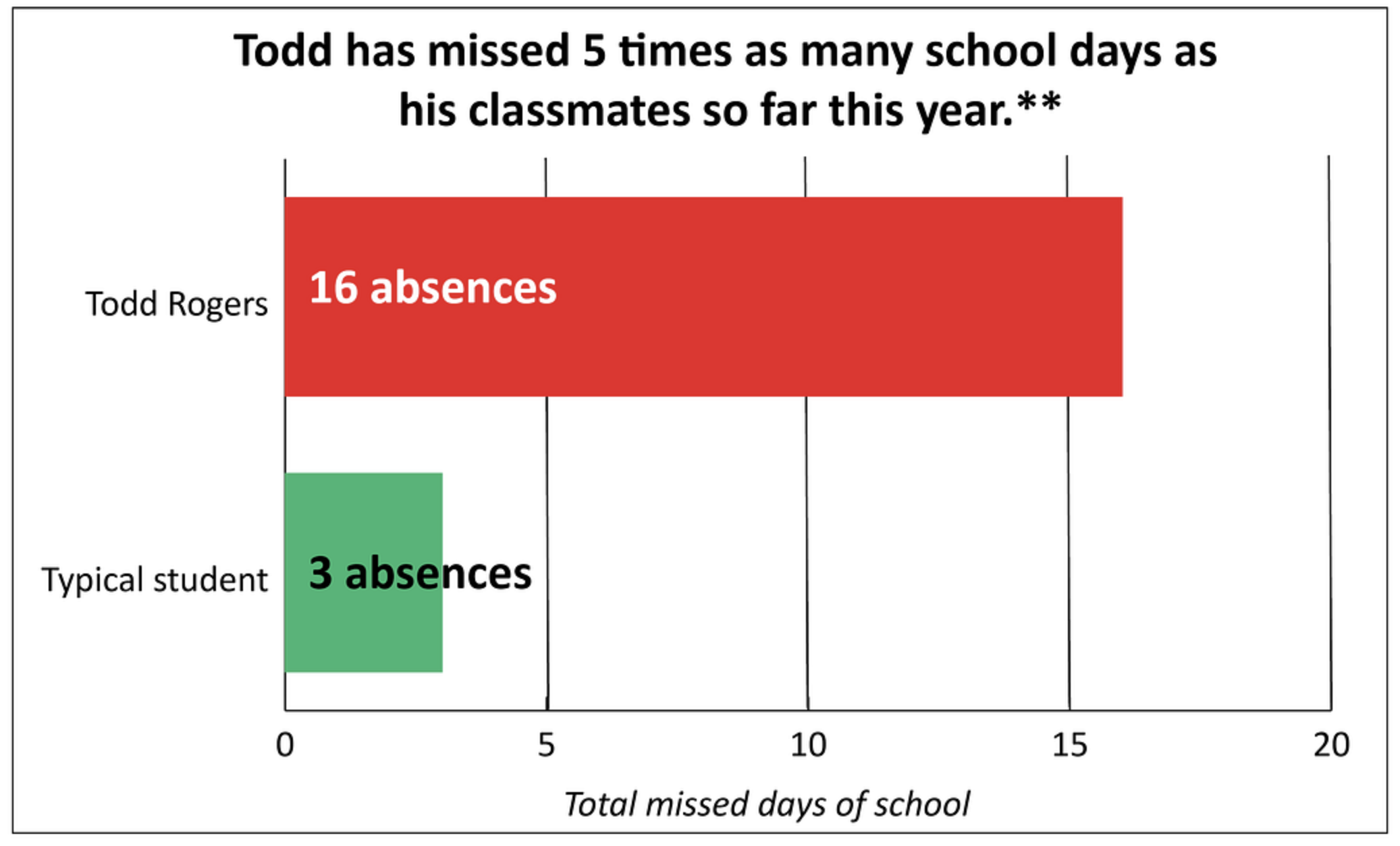

The Harvard behavioural scientist Todd Rogers has achieved great results in reducing student absenteeism at school by telling parents of chronically absent kids how much school their child is missing, and how much higher than average that number is:

Parents had often underestimated how many days their children were missing, and mistakenly believed that they were close to the average. A simple message telling them otherwise reduced chronic absenteeism by 10%.

Note: Sometimes you can't target your message just at people who are underperforming, and instead have to give the information to everyone. There is a danger here that if you tell the best people that they're above average, they will start doing worse. If my child is never absent from school and I find out that their peers have missed 3 days, perhaps that cheap deal on a term-time holiday starts to look a lot more tempting.

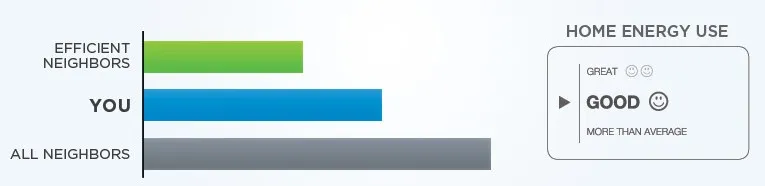

One strategy to avoid this kind of backfire effect is by providing some positive or negative interpretation alongside the objective numbers: if I'm doing well, tell me so. Here we are moving beyond a simple descriptive norm—"What do most people do?"—to an 'injunctive' norm: "What is approved of?". A simple smiley face can serve this purpose, as in this classic study with power company Opower:

Lots of people do this

But what do we do if the average is bad? What if most people are doing the wrong thing? Faced with this situation, many people's first instinct is to run a campaign about how big the problem is and how bad the consequences will be unless everyone mends their ways: "Most people are skipping the fare on the subway: if this continues our public transport system will go bust!".

Messages like this are often a BAD IDEA. The implicit social norm message is that most other people are avoiding the fare, that doing so is normal, so I'd be an idiot not to. It's a shame about the city going broke, but my fare isn't going to make the difference either way.

A better idea is to adapt our tactics. If the average is unfavourable, we can instead look at the 'dispersion' of results: are there pockets of good behaviour that we can highlight?

On college campuses, student drinking is widespread, and students are aware of this. But what students are sometimes not aware of is that there are still significant numbers of their peers who drink in moderation or not at all. In a large student body, this can be hundreds or thousands of students. A reminder that lots of their fellow students don't drink much can be an effective intervention, giving students more social license to make their own choice as they feel comfortable.

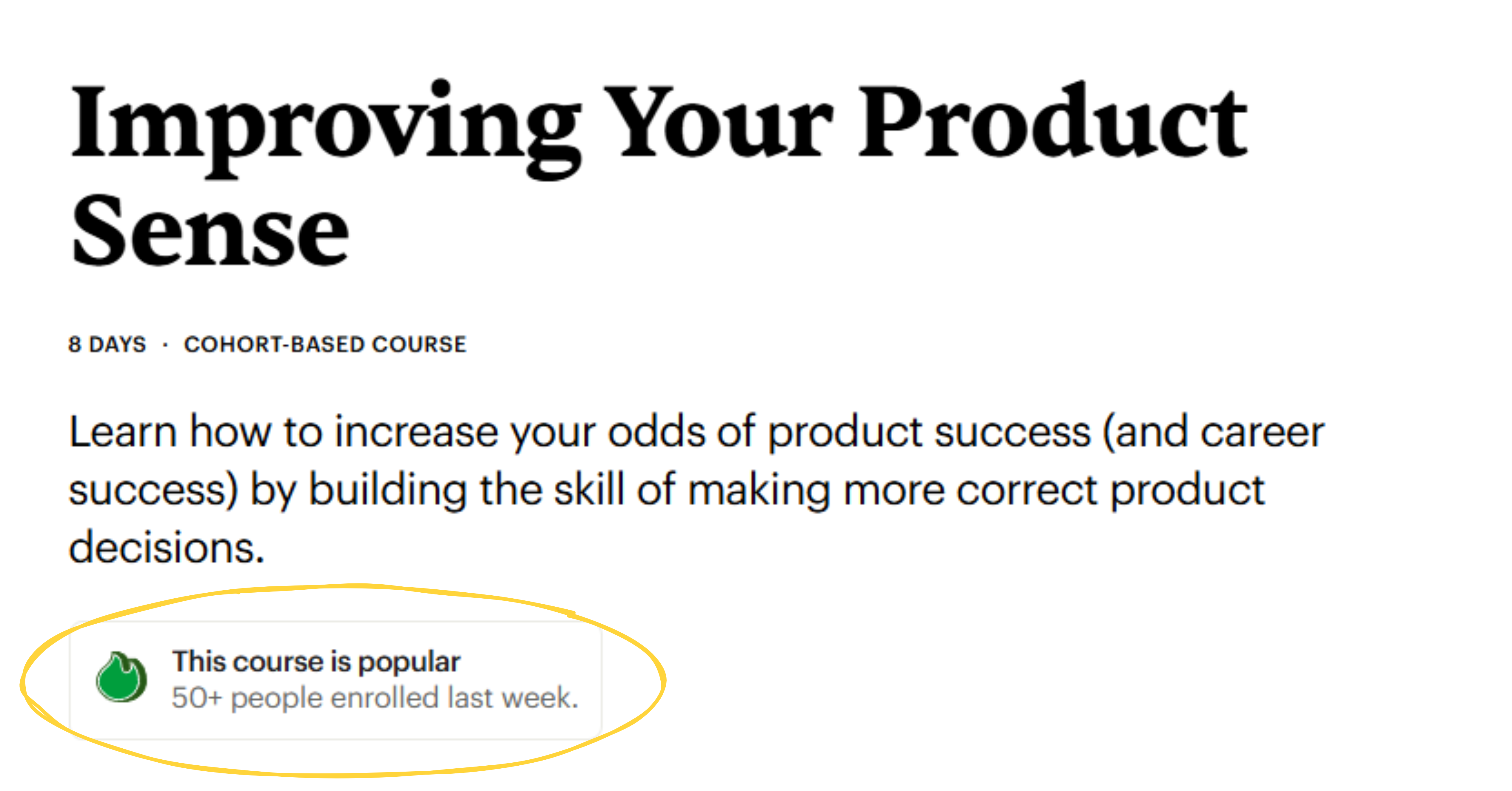

You will also notice messaging with large numbers rather than proportions used a lot in commercial settings. Often there isn't a meaningful population to make an average from: if a shop has 1,000 customers, expressing that as "0.01% of the people in New York shop here" is not the most persuasive. Instead, just providing some absolute number can help provide that social context to people. Here is an example from the online course provider Maven:

'Thousands of happy users' is another effective format:

More and more people are doing this

Another strategy if the average is unfavourable is to look at the trends. Perhaps not many people are doing a behaviour. But are more doing it than yesterday? If so, the resulting sense of social momentum - that a norm is shifting - can be very motivating.

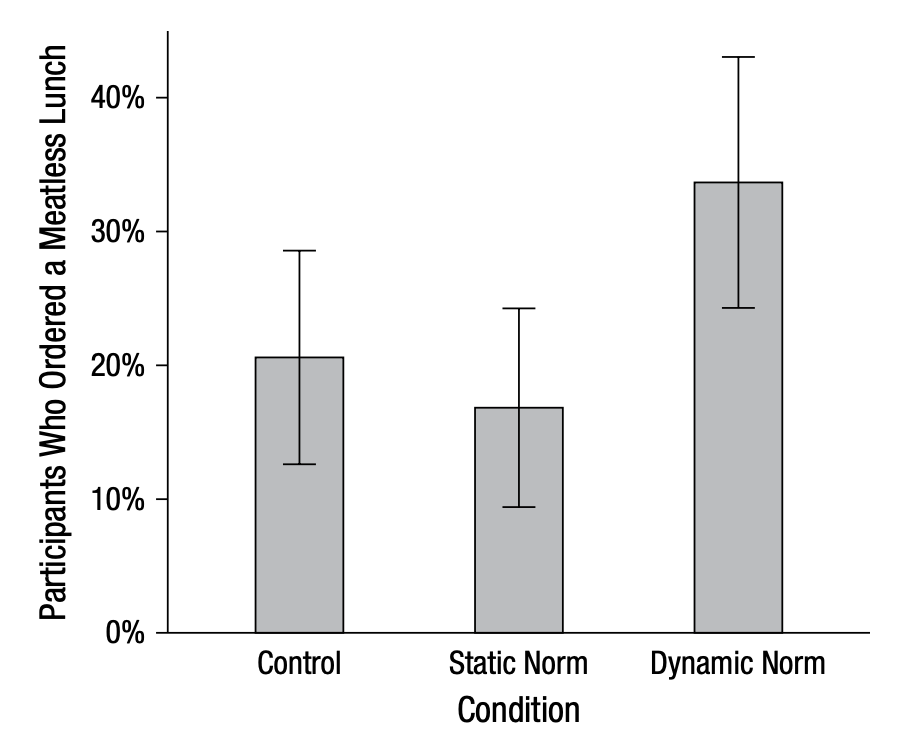

In 2017 Gregg Sparkman and Gregory Walton published a series of experiments on meat consumption in the US. Meat eating is overwhelmingly the norm, but the researchers were able to use a statistic showing that 30% of Americans now make an effort to limit their meat consumption. On its own, this fact was not persuasive (the 'static norm' bar below). But emphasising that this was a new development, that this change had happened only in recent years (the 'dynamic norm' bar below), significantly increased participants chances of ordering a meatless lunch:

An advanced variant of this is the phenomenon of 'pluralistic ignorance'. Pluralistic ignorance occurs when most people privately reject a norm but incorrectly believe that most people around them are in favour, and hesitate to voice their views as a result. Situations like this can go on a long time, but they are unstable: if the dam breaks and people start to say how they really feel, others feel emboldened to join them, and the norm can quickly flip (what might be called a 'vibe shift' in modern parlance).

Smart social norm messaging can accelerate this shift. In 2018, for example, Bursztun et al. conducted research with young married men in Saudi Arabia showing that most privately supported female participation in the labour force. But they each thought themselves unusual in that view, and expected their peers to be against it. Correcting that misperception significantly increased their willingness to let their wives join the labour force: more of them signed up for a job-matching service for their wives, and four months later their wives were much more likely to have applied and interviewed for a job outside of home.

Here's an example of someone who does this

If all else fails, a single example of someone doing a behaviour is enough to make it seem more normal, less weird, and more accessible.

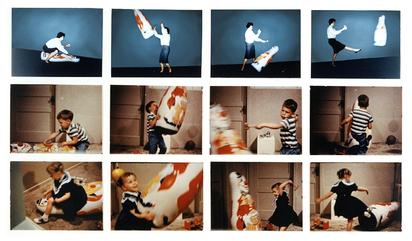

Psychologist Al Bandura’s studies on 'social modelling' in the 1960s showed that seeing just one person engage in a behaviour can shape our perception of “what’s normal” or “what’s possible.” Children who observed an adult treating an inflatable 'Bobo doll' (pictured below) aggressively were more likely to imitate that aggressive behaviour themselves later on. Just one role model had an outsize effect on what the children perceived as normal or acceptable.

Many successful adverts are built around a demonstration of the key behaviour. A famous example from the political world was the 1997 UK Labour Party broadcast which shows the point-of-view of a man (revealed at the end to be Tony Blair himself) voting. Every step is shown, from receiving his polling card in the mail, to walking to the polling station, to filling out the ballot, to posting it in the ballot box. Modelling a behaviour like this makes it seem normal and easy ('psychologically available', in the jargon):

In more modern contexts, a very useful tactic on a website is to include a screen recording of someone signing up for or using the service in question, to show how easy it is. Here's a simple example from GPTExcel, an AI formula-writing app:

Conclusion

The social norm messages above are of course just the starting point. Part of what makes humans such a smart and successful species is our ability to learn from others around us, and we are attuned to all sorts of subtle signals in our environment. These include everything from what the rules are, what people in authority are saying and doing, what we see on TV and social media, what our physical surroundings look like, and what we directly observe of our friends, parents, colleagues, and spouses.

We will be exploring how to add these other angles to your social norms repertoire in future editions of this guide. Sign up below to receive updates as they get published:

The strategies described above are nonetheless a strong starting point. A social norms message should nearly always be on your longlist when rewriting a letter. Questions about the prevailing social norms ("What do your neighbours do?", "What do your friends think about it", "What do the data say?") should be near the top of your list when trying to diagnose a behaviour you don't understand. And they're a good thing to train yourself to notice about the world around you: you'll be a better intuitive behavioural scientist as a result.

Further Reading

Tankard, M. E., & Paluck, E. L. (2016). Norm perception as a vehicle for social change. Social Issues and Policy Review, 10(1), 181-211.

Sparkman, G., & Walton, G. M. (2017). Dynamic norms promote sustainable behavior, even if it is counternormative. Psychological science, 28(11), 1663-1674.